Nautical Museum – THE PEGGY

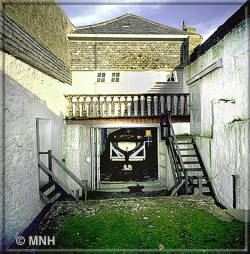

Returning to the landing, a stair leads to the boat cellar and Peggy herself. She has rested here undisturbed for more than a century and a half, and at some point in that time the opening through which she used to pass into the harbour was walled up, and the ground filled in within the enclosure, cutting her off for ever from her natural element.

Returning to the landing, a stair leads to the boat cellar and Peggy herself. She has rested here undisturbed for more than a century and a half, and at some point in that time the opening through which she used to pass into the harbour was walled up, and the ground filled in within the enclosure, cutting her off for ever from her natural element.

For many years almost forgotten, in 195, she was “re-discovered”, and immediately seen by nautical enthusiasts to be of the greatest interest. The Society for Nautical Research made a detailed record of her, and plans and photographs were exhibited at the Science Museum, South Kensington.

In 1941, when Bridge House, the old home and town-house of the Quayles was sold, the Peggy was presented to the Manx Museum Trustees, together with the boathouse, but it was not until 1950 that it became possible to undertake the necessary repairs to her. Happily, she had survived her long confinement almost intact, and only the keel, the stern post and two planks of the hull where she had lain on her starboard side, required replacement. She was repaired by local craftsmen and placed in a cradle. (Her original keel is now preserved in the loft of the Nautical Museum.) Finally, in 1951, the Trustees were able, with the aid of much generous support, to put the Nautical Museum and the Peggy on view to the public.

Built in 1789, the Peggy was a schooner-rigged, clinker-built yacht 26ft 5ins overall length, 7ft 8ins beam, with an inside depth of 6ft. The Admiralty licence which was issued to her in 1793 describes her as of 6.5 tons burthen, and details her armament as six small swivels and six fowling pieces. In fact, she was equipped with eight cannon, six 1ft long mounted three a side, and two slightly longer as stern chasers.

Built in 1789, the Peggy was a schooner-rigged, clinker-built yacht 26ft 5ins overall length, 7ft 8ins beam, with an inside depth of 6ft. The Admiralty licence which was issued to her in 1793 describes her as of 6.5 tons burthen, and details her armament as six small swivels and six fowling pieces. In fact, she was equipped with eight cannon, six 1ft long mounted three a side, and two slightly longer as stern chasers.

Her main planking was of pine. The planks vary in width from 6in to 8in and are 7/8in thick. The rubbing strakes on the three top planks appear to be of teak, the same wood being used for the moulding on the transom. Hull fastenings throughout consist of heavy iron bolts. Ribs and floors are of oak. Floors are approximately 7in deep and 1in thick amidships, the size being reduced to only 3.5 in deep and 1.5 in thick in the forward floors.

Most of the spars and both the masts are still intact, so it has been possible to reconstruct her sail plan with some accuracy. The rig appears to have consisted of a gaff mainsail, a gaff foresail, and a jib, and was probably very like that of a schooner yacht shown in the painting of 1772 of Captain Cook’s expedition leaving the Downs. The size of the Peggy was probably determined by the man o’ war launch of her day – general dimensions are about the size of the Bounty’s launch in which Captain Bligh made his amazing 4,000 mile voyage. Her lines, however, have a much more streamlined appearance and she was undoubtedly much faster.

Unusual features which made her an advanced boat for her day were her drop keels (called “sliding keels” by Quayle), the slots for which can be seen, and which made her much more manoeuverable. Her transom stern is a particularly attractive one; the paintwork has survived and has been carefully preserved, with its decorative motif and the inscription George Quayle Castletown. An earlier phase of the decoration of the stern can just be made out, with the name “PEGGY” in gilt on a green background. Altogether, the Peggy is a fine craft, and full of historic interest, showing as she does the skill and knowledge of her builders in her durability and the excellence of her design.

It may seem strange that this little pleasure craft was equipped with eight small cannon – not to mention “half-a-dozen fowling pieces” but when the Peggy was built, wars with the French were once more in the offing, and the seas about the Island were at such times the haunt of privateers. In such circumstances, it is in keeping with what we know of her owner, that he should have equipped her with these little brass guns.

It may seem strange that this little pleasure craft was equipped with eight small cannon – not to mention “half-a-dozen fowling pieces” but when the Peggy was built, wars with the French were once more in the offing, and the seas about the Island were at such times the haunt of privateers. In such circumstances, it is in keeping with what we know of her owner, that he should have equipped her with these little brass guns.

In fact, she appears to have gone her way unmolested in her voyages about the Irish Sea, and she must have made the trip to England on many occasions. A record exists of one of these, for in 1796 she sailed to and from a regatta on Lake Windermere, where according to George Quayle, she aroused interest and achieved success:

“.. the long bolsprit (i.e. bowsprit) and sliding keels have already produced strong symptoms of scisme among the devotees of freshwater sailing. Captain Heywood’s boat is the second best in the Lake – modesty prevents me from saying who bears the bell. . . “

The return journey in very rough weather put the Peggy and her skipper to the test, and with the tide and gale against him, he debated whether to run for Liverpool or Wales, but:

“. . . we put down the sliding keels and that enabled us to stand on, now and then letting fly the foresail and continuing our tack we fetched about three leagues of the leeward of the Calf. The wind now changed to the westward and by one tack we fetched this (Castletown) Bay . . . the quarter cloths were of very great protection, without them I believe we had gone to Davy Jones’s locker, and without the sliding keels we could not have carried sail enough.”

How many other stories could the Peggy tell of storms weathered and safe harbour reached, before she swallowed the anchor and came to rest finally in her berth, to bear witness today to the long history of Manx seamanship.